Egypt

Last updated: February 2022

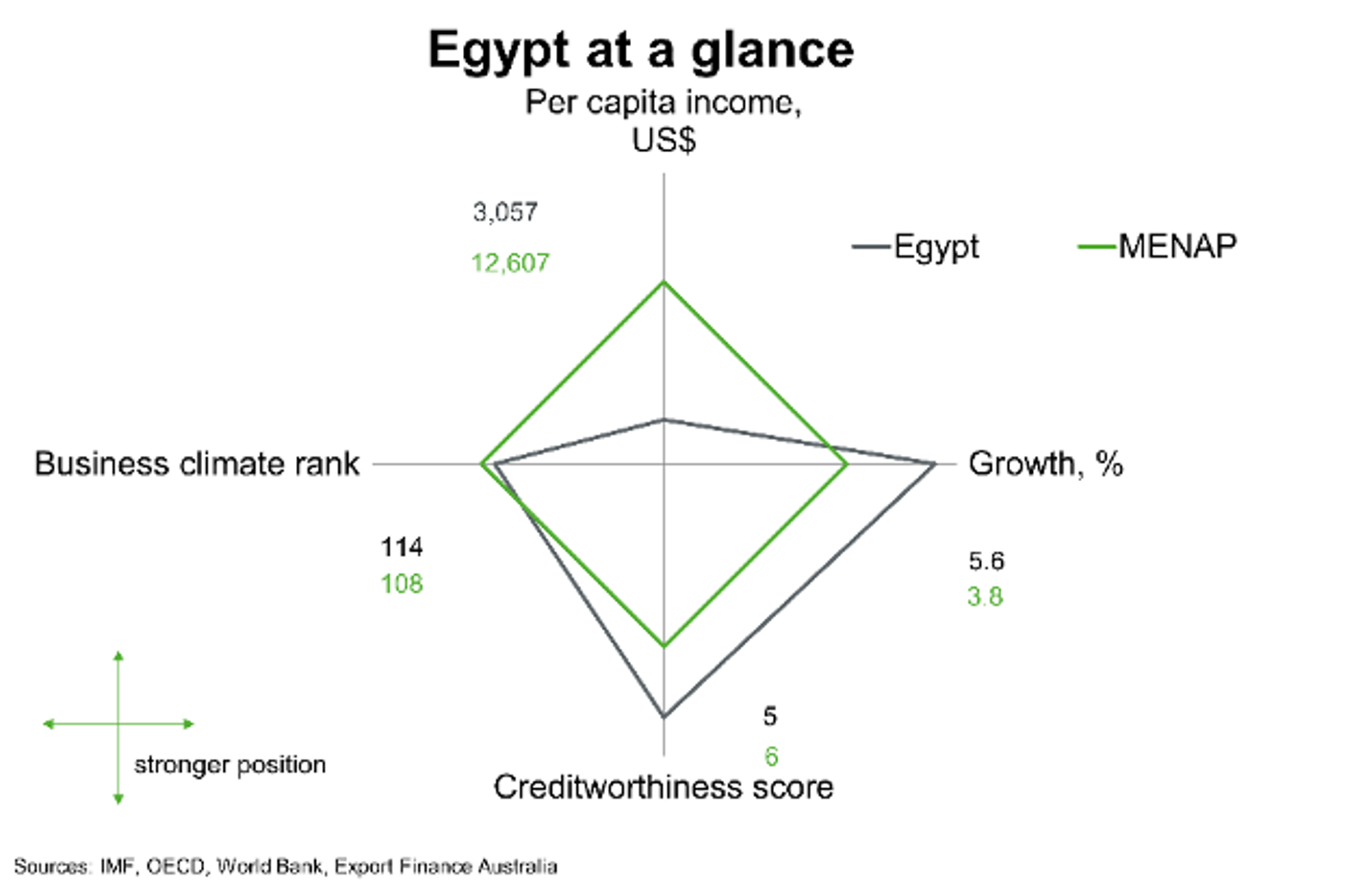

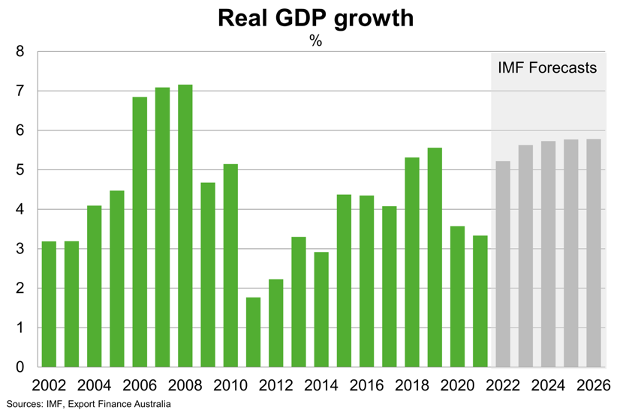

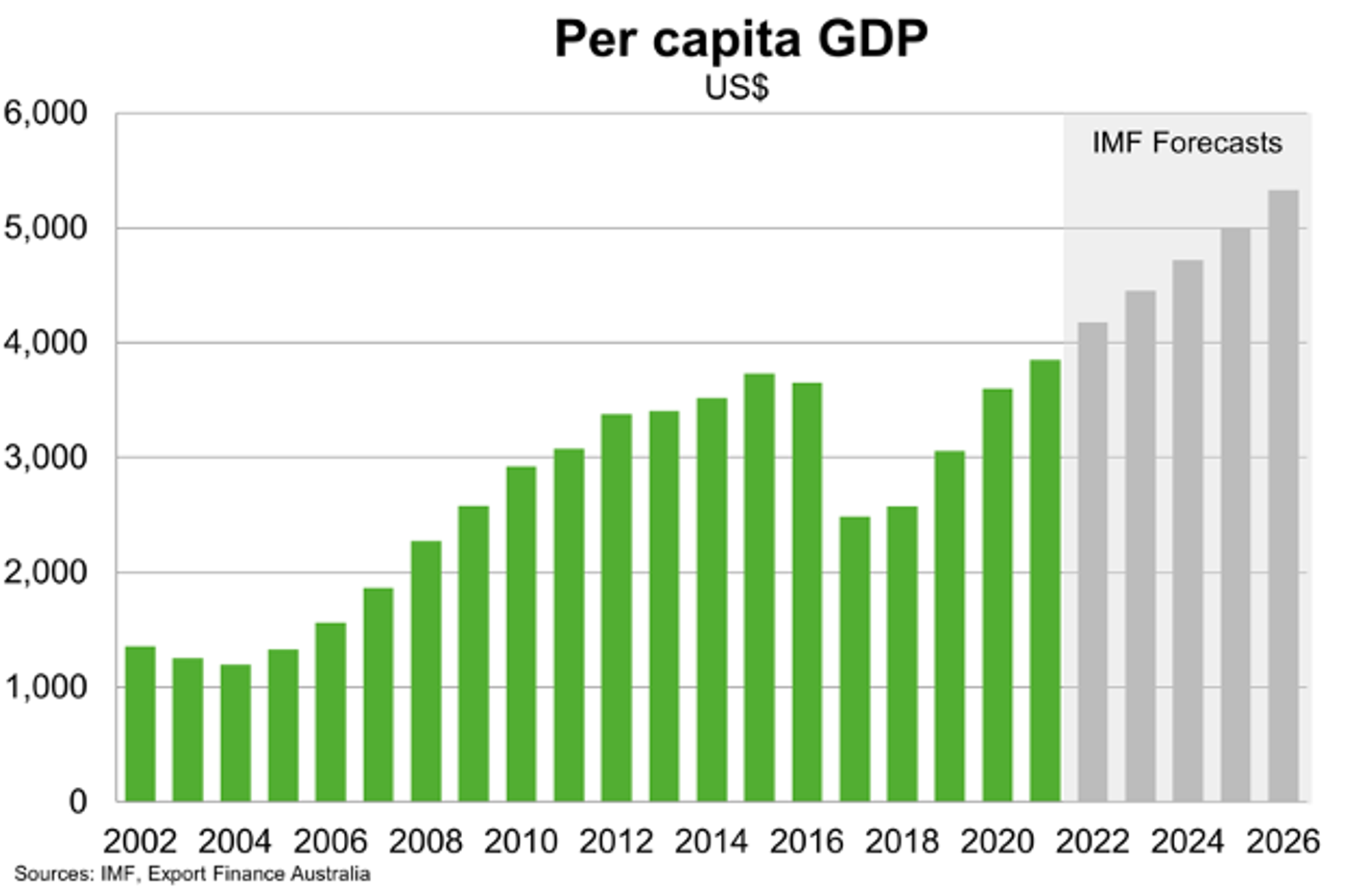

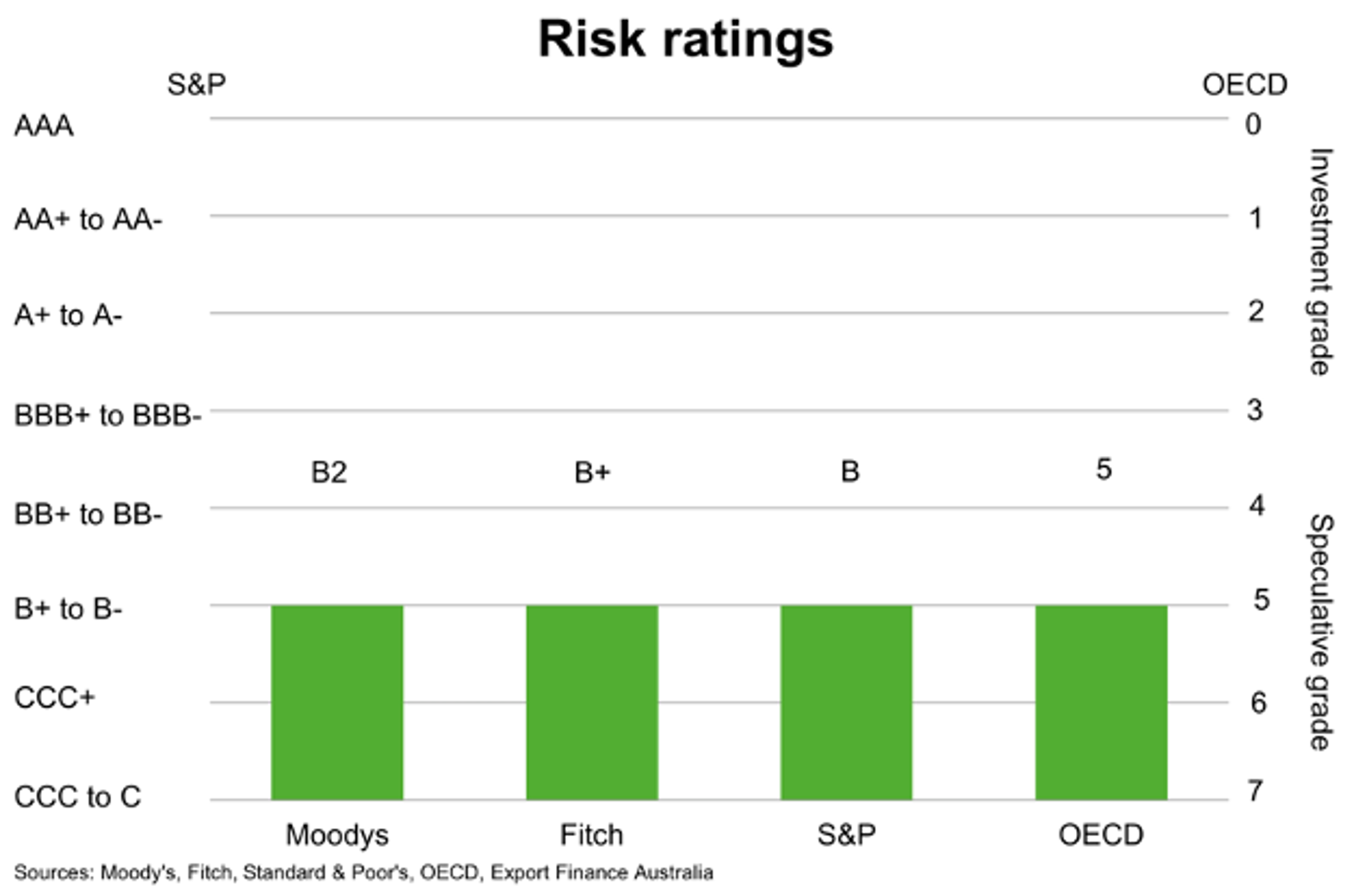

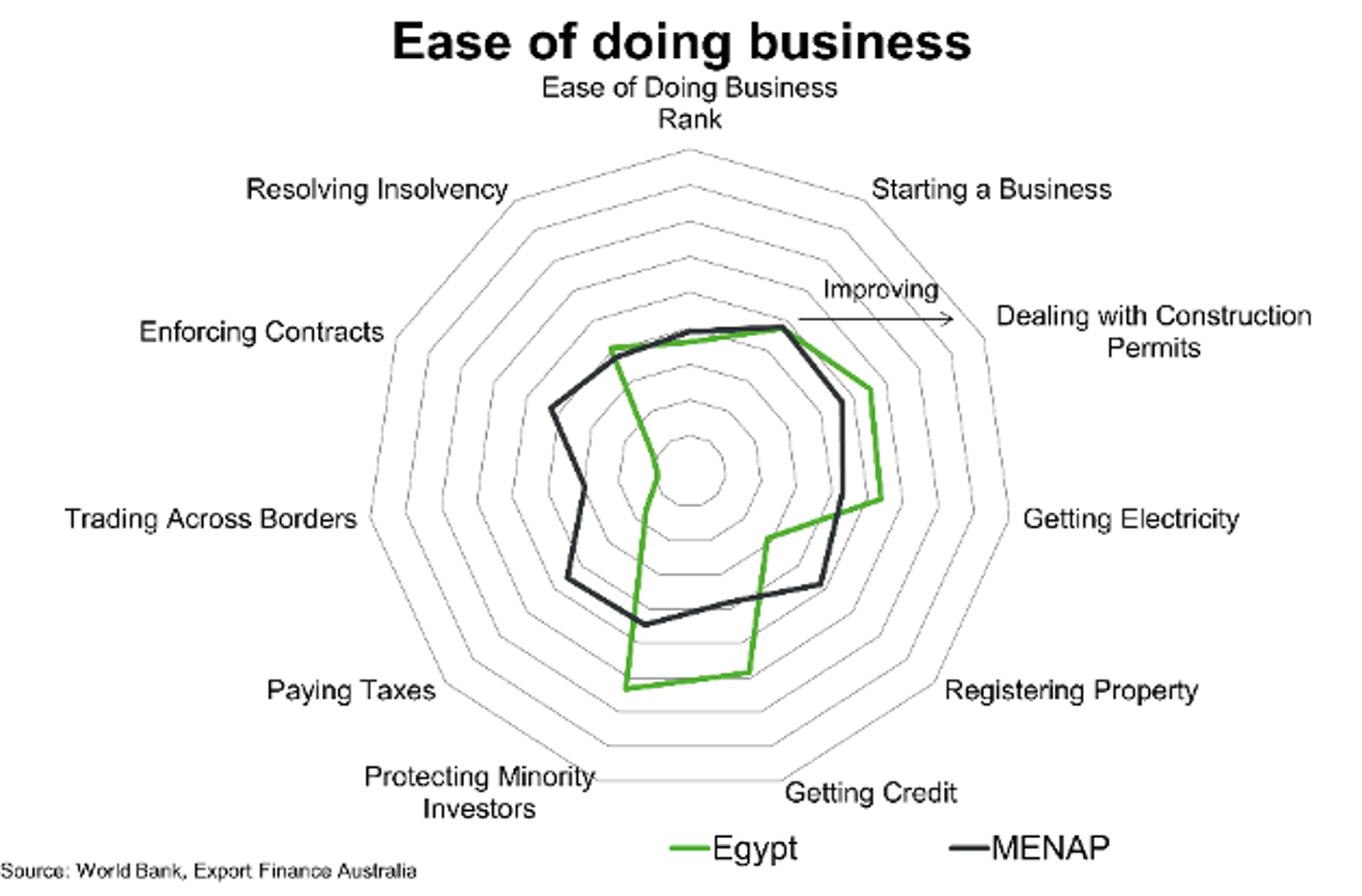

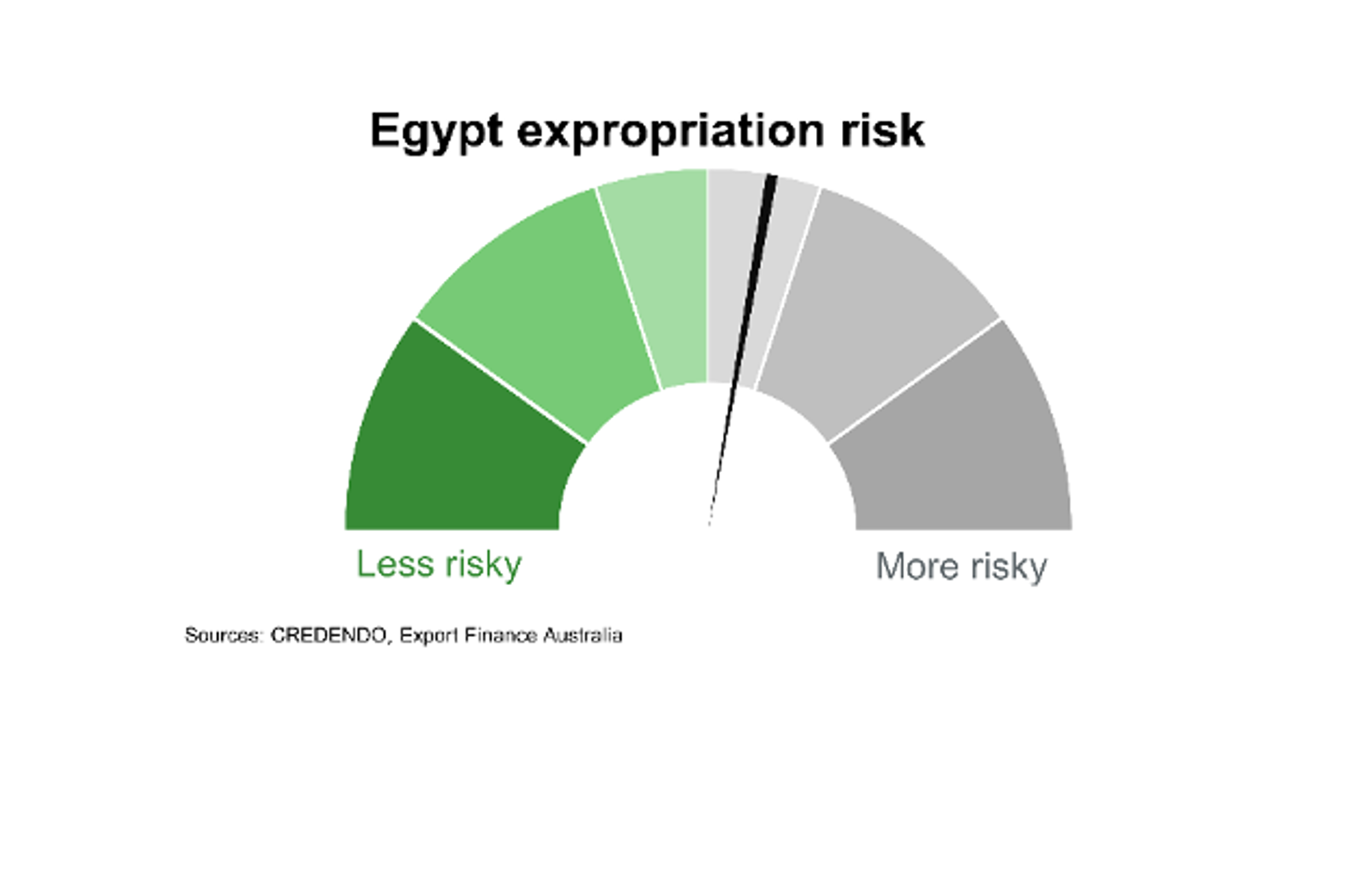

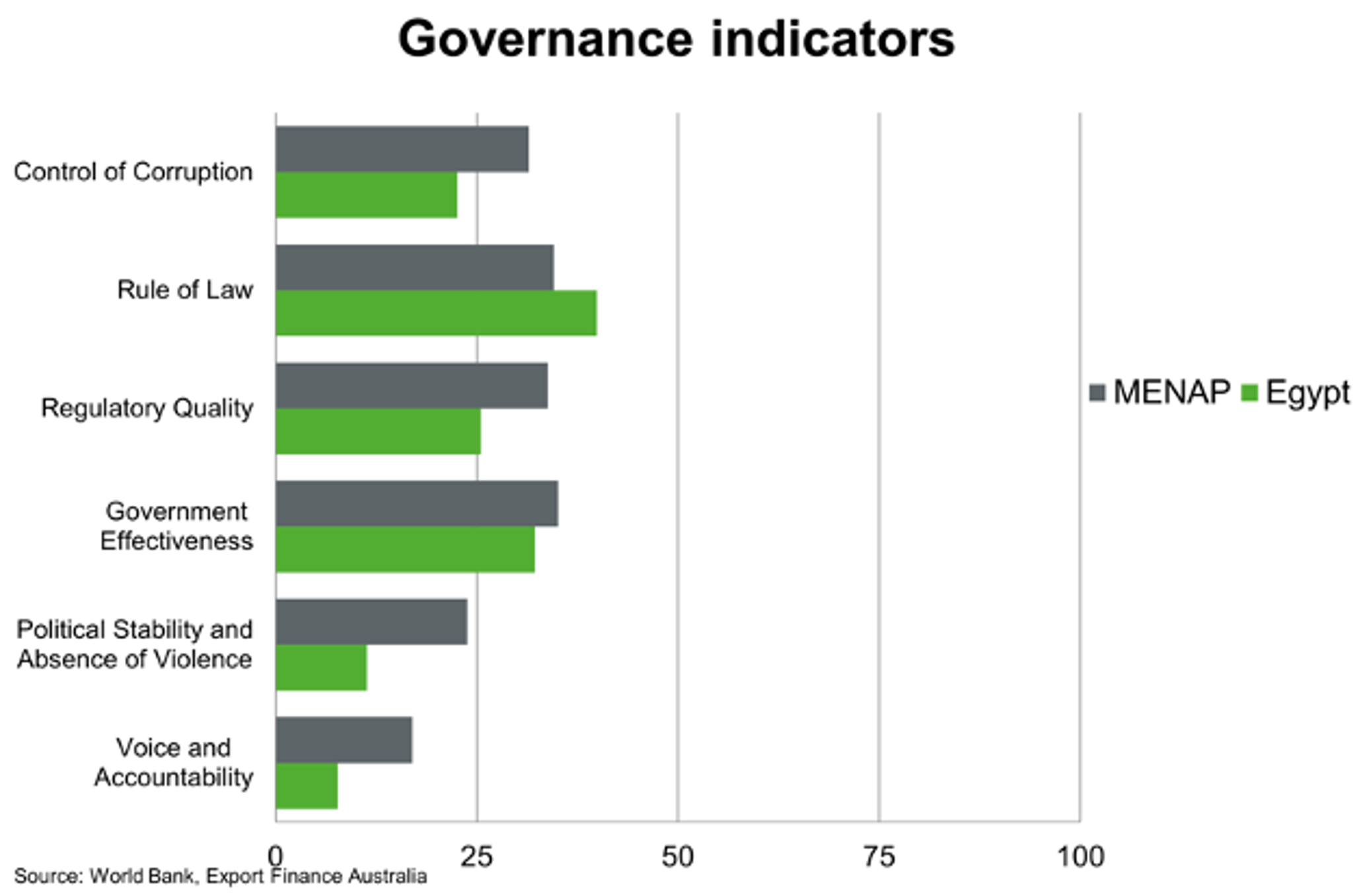

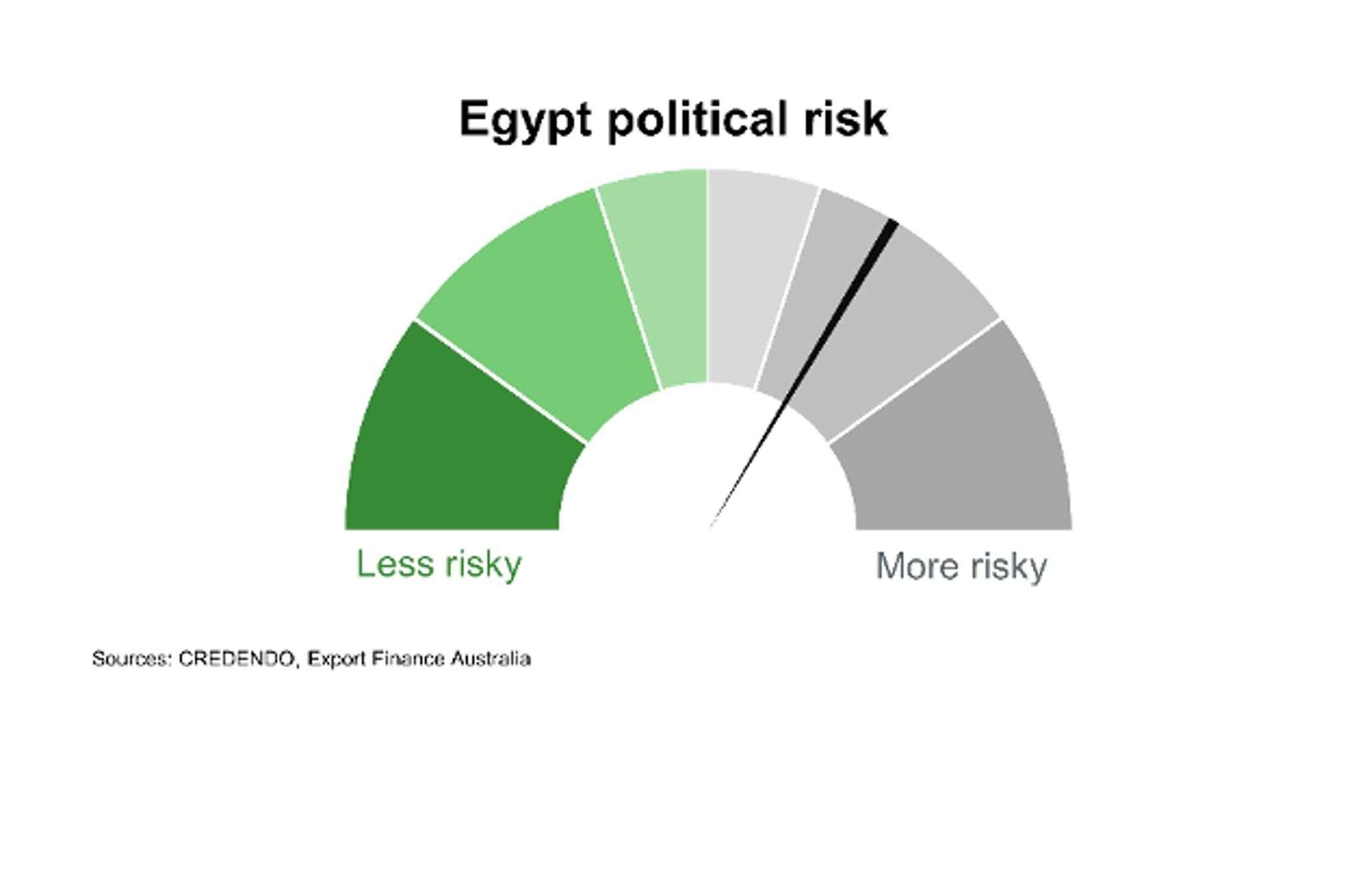

Egypt performs similarly to other Middle Eastern countries on measures of growth, creditworthiness and business climate. But per capita incomes lag significantly behind peers such as Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar. Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic outlook is supported by production and investment in extractive industries. Ongoing support from the IMF will facilitate continued economic and fiscal reforms that enhances the business environment and encourages investment.